Paper first appeared in China in the second century BCE (Hansen, 5). It was first used as a wrapping material and not for writing. Paper began to be widely used as a writing material four centuries later in the second century CE (Hansen, 15). It moved out of China through the silk road and into the middle east by the eighth century CE. It was not until much later, in the fourteenth century, when the first paper mills appeared in Europe (Hansen, 6). Prior to paper, materials like leaves, turtle shells, animal bones, hide, wood, bamboo, and silk were all used as writing materials (Su-il, 638). Plant based paper was easier to mass produce and had a consistent shape and size (Su-il, 640). Papyrus was also used to make paper; however, it was only produced in Egypt, and it was bulkier than Chinese paper (Su-il, 639). [1]

Paper became a desirable material because it was lightweight and could hold many characters. It was also an expensive material that people did not want to waste. Scrap paper was saved and used to repair documents, and the margins were often used by students practicing their writing (Hansen, 301). Even if one side of a sheet of paper had writing, it could still be sold and the opposite side used (Hansen, 138). Paper was also recycled into shoes, clothing, and statues to accompany the dead (Hansen, 4). These recycled documents used for the dead, although incomplete, have given us a lot of information in Silk Rod trade and communities (Hansen, 4). [2]

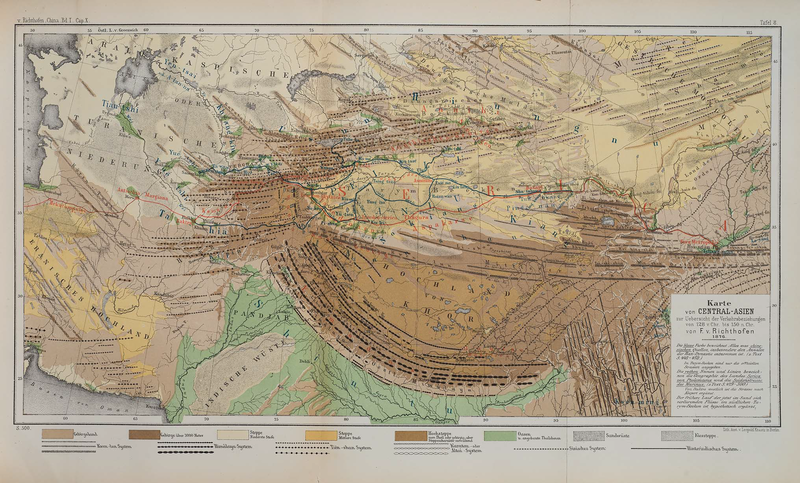

It is only because of surviving documents that we have so much information on the silk road economy. It is rare to find paper documents because the organic material tends to break down, however, the dry climate of the Taklamakan Desert is perfect for their preservation (Helman-Wazny, 127). The information in these documents come from a variety of sources, not just the ruling class. Most documents have been preserved on accident. They contain records of itemized goods and other seemingly mundane information. They have been found in places like abandoned postal stations, tombs, shrines, homes, and even garbage pits (Hansen 5). The glimpse that they give us into the everyday activities is invaluable when piecing together the history of the Silk Road.

Paper could be made from different materials to create a specific desired effect. The most common materials used were rags, hemp, mulberry, ramie, flax, cotton, and phloem from trees (Helman-Wazny, 133). The raw materials were soaked in water and boiled to loosen the fibers of the plant. Once there is adequate separation the fibers are beaten upon a stone with a mallet to create a finer pulp mixture. Using the dipping method, the pulp is suspended in water and a screen mold is dipped in to collect an even layer of fibers. The page is then taken off the screen and set aside to airdry. Using this method, papermakers could produce paper much faster (Helman-Wazny, 128). There was a lot of skill required to make paper and specific techniques were required give the paper certain properties, like aligning the fibers in the same direction (Helman-Wazny, 130).

Here is some more text below the images.[3]

[1] This is the text of footnote one.

[2] This is the text of footnote two.

[3] This is the text of footnote three.

Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road : A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2012.

Helman-Ważny, Agnieszka. “More Than Meets the Eye: Fibre and Paper Analysis of the Chinese Manuscripts from the Silk Roads.” Science and technology of archaeological research 2, no. 2 (2016): 127–140.

Su-il, Jeong. The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Irvine, CA: Seoul Selection, 2017.